Chapter 3: Second and Higher Order Differential Equations, Kohler & Johnson 2e

3.1 Second Order Differential Equations

Second order differential equation: \(\displaystyle \frac{d^2y}{dt^2}=f\left(t,y,\frac{dy}{dt}\right)\)

Linear: \(\displaystyle f\left(t,y,\frac{dy}{dt}\right)=G(t)-p(t)\frac{dy}{dt}-q(t)y\)

In general we write:

\[y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=G(t)\]

Or if we have an initial value problem:

\[y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=G(t),\qquad y(t_0)=y_0,\qquad y'(t_0)=y_0',\qquad a<t<b\]

Note: \(g(t)\), \(p(t)\) and \(q(t)\) are continuous functions of \(t\) on \(a < t < b\).

There are two types: homogeneous if \(G(t) = 0\) and nonhomogeneous if \(G(t) \neq 0\).

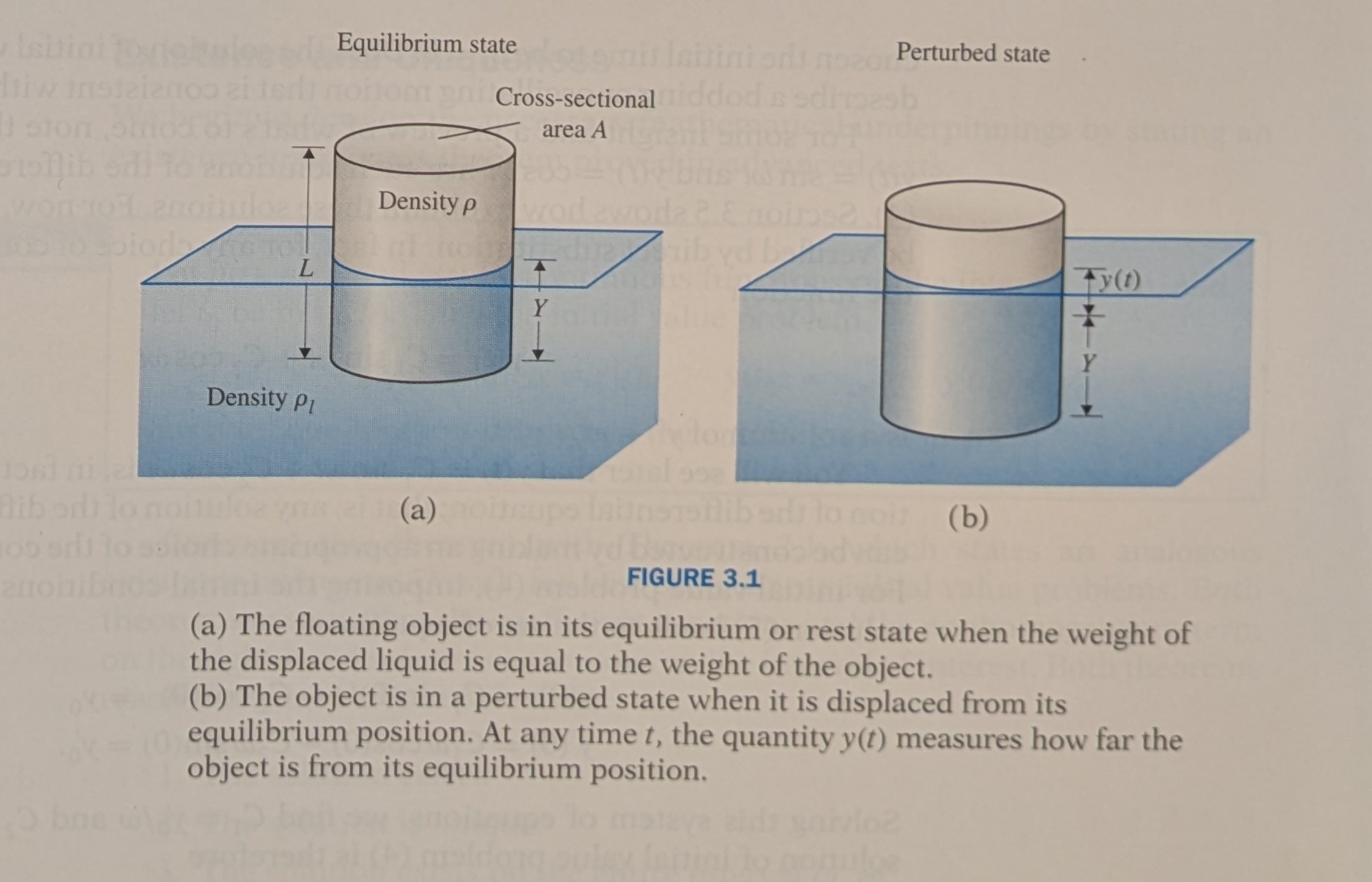

An Example: The Bobbing Motion of a Floating Object

We will begin modeling the behavior of a simple physical system: The bobbing motion of a floating object. The buoyant force on an object in liquid is equal to the weight of the displaced liquid. So in its rest or equilibrium state, a floating object is subjected to two equal and opposite forces: the weight of the object and the weight of the liquid.

Consider the objects shown in figure 3.1. The object has a uniform mass density \(\rho\), constant cross sectional area \(A\), and height \(L\). The density of the liquid is \(\rho_{l}\). If we wish to model the equilibrium solution we set the weight of the liquid = the weight of the object.

\[\rho_l AYg=\rho ALg \tag{3.1}\]

\[Y=\frac{\rho }{\rho_l}L\]

We would like to write an equation that models the motion of the object if it is given some displacement \(y(t)\). Newton’s law of motion says \(\sum F=ma\).

We can use this idea to write equations for the forces acting on the object:

The weight of the object: \(\rho ALg\)

The buoyant force of the liquid \(\rho_l Ag(Y+y(t))\)

And the acceleration is the second derivative of the position \(\displaystyle \frac{d^2}{dt^2}(Y+y(t))\) and the mass is \(\rho AL\) so we can write:

\[\Sigma F = m a\]

\[\rho ALg-\rho_l A(Y+y(t))g = \rho AL\frac{d^2}{dt^2}(Y+y(t))\]

Substituting equation (3.1) and taking the derivative on the left we get:

\[\rho ALy''(t)=-\rho_lAy(t)g\]

After some algebraic manipulation we simplify the equation to:

\[y''(t)+\omega^2y(t)=0 \qquad \text{where} \qquad \omega^2=\frac{\rho_l g}{\rho L}\]

We will also apply the initial conditions \(y(0)=y_0\) and \(y'(0)=y_0'\).

It turns out (we will see why later) that the solution to this equation is:

\[y(t)=C_1 \sin (\omega t)+C_2 \cos (\omega t)\]

where the constants are determined by the initial conditions. Solving for the constants gives us that \(C_1=y_0'/\omega\) and \(C_2=y_0\) so the solution is:

\[y(t)=\frac{y_0'}{\omega}\sin (\omega t)+y_0\cos (\omega t) \text{ where } \omega^2=\frac{\rho_lg}{\rho L}\]

Existence and Uniqueness

- Make the IVP look like the formula in Theorem 1.

\[y''-\frac{3t}{(t-1)}y'+\frac{4}{(t-1)}y=\frac{\sin t}{(t-1)}\]

Find where \(p(t)\), \(q(t)\) and \(g(t)\) are continuous.

Choose the appropriate interval which includes the initial \(t_0\)

3.2 The General Solutions of Homogeneous Equations

We will start by looking at solutions of the homogeneous equation:

\[y'' +p(t) y' +q(t) y = 0\]

where \(p(t)\) and \(q(t)\) are continuous on \((a,b)\).

Definition: Let \(f_1(t)\) and \(f_2(t)\) be any two functions having a common domain, and let \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) be any two constants. Then the function \(F(t) = c_1 f_1(t)+ c_2 f_2(t)\) is a linear combination of \(f_1(t)\) and \(f_2(t)\). We can extend the definition in the obvious way to describe any number of functions.

Proof: For simplicity we will assume \(C_1 = C_2 =1\) but if you include those the proof is the same.

\[\begin{array}{l} y = y_1+y_2\\ y' = y_1'+y_2'\\ y'' =y_1''+y_2''\\ \end{array}\]

Substitute back into \(y'' +p(t) y' +q(t) y = 0\) to get:

\[y_1''+y_2'' +p(t) (y_1'+y_2') +q(t) (y_1+y_2) =\underbrace{y_1''+p(t) y_1' +q(t) y_1}_{=0} +\underbrace{y_2'' +p(t) y_2' +q(t) y_2}_{=0} = 0\]

QED

Consider \(y'' +p(t) y' +q(t) y = 0\) with the initial conditions \(y(t_0)=y_0\), \(y'(t_0)=y_0'\). If we start with 2 solutions \(y_1\) and \(y_2\) then \(y=C_1 y_1 +C_2 y_2\) is also a solution and we can solve for the constants \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) by using the initial conditions. We get a system of equations:

\[\begin{align*} y_0 &= C_1 y_1(t_0) + C_2 y_2(t_0) \\ y_0' &= C_1 y_1'(t_0) + C_2 y_2'(t_0) \end{align*}\]

We can use Cramer’s Rule to solve the system:

\[C_1=\frac{ \det\begin{bmatrix} y_0 & y_2(t_0) \\ y_0' & y_2'(t_0)\\ \end{bmatrix} }{\det\begin{bmatrix} y_1(t_0) & y_2(t_0) \\ y_1'(t_0) & y_2'(t_0)\\ \end{bmatrix}} \quad \text{and} \quad C_2=\frac{ \det\begin{bmatrix} y_1(t_0) & y_0 \\ y_1'(t_0) &y_0' \\ \end{bmatrix} }{\det\begin{bmatrix} y_1(t_0) & y_2(t_0) \\ y_1'(t_0) & y_2'(t_0)\\ \end{bmatrix}}\]

Notice that \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) have solutions as long as:

\[\det\begin{bmatrix} y_1(t_0) & y_2(t_0) \\ y_1'(t_0) & y_2'(t_0)\\ \end{bmatrix} \neq 0\]

or \(y_1(t_0) y_2'(t_0) - y_2(t_0) y_1'(t_0) \neq 0\)

This determinant is known as the Wronskian:

\[W(t) =\det\begin{bmatrix} y_1(t) & y_2(t) \\ y_1'(t) & y_2'(t)\\ \end{bmatrix}\]

Why do we care about Abel’s Theorem? Because it says that if the Wronskian is not zero at any point of \((a, b)\) then it is not zero at every point of \((a, b)\).

Part 1: \(y''+y=0\); \(y_1(t) = \sin t \cos t\), \(y_2(t) = \sin t\); \(y\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right) = 1\) and \(y'\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right) = 1\)

Part 2: \(y''-4y'+4y=0\); \(y_1(t) = e^{2t}\), \(y_2(t) = te^{2t}\); \(y(0) = 2\) and \(y'(0) = 0\)

Part 3: \(ty'+y=0\), \(0<t<\infty\); \(y_1(t) = \ln t\), \(y_2(t) = \ln (3t)\); \(y(3) = 0\) and \(y'(3) = 3\)

Part 4: \(4y''+y=0\); \(y_1(t) = \sin (t/2 +\pi/3)\), \(y_2(t) = \sin (t/2 -\pi/3)\); \(y(0) = 0\) and \(y'(0) = 1\)

3.3 Constant Coefficient Differential Equations

We will begin with linear, homogeneous, 2nd order differential equation with constant coefficients. This means an equation of the form:

\[a y'' +b y' +c y = 0 \qquad \text{where } a, b, \text{ and } c \text{ are constants.}\]

If we start with something like \(y'' - y = 0\) then we have two obvious solutions:

\[\begin{array}{l} y_1 = C_1 e^{t} \\ y_2 = C_2 e^{-t} \end{array}\]

Now consider the more general case \(a y'' +b y' +c y = 0\). A solution to this equation could be of the form:

\[y = e^{rt}\]

To see that this is a solution we will take two derivatives and substitute back into the original equation:

\[\begin{array}{l} y' = re^{rt}\\ y'' = r^2 e^{rt}\\ \end{array}\]

So if we substitute back into \(a y'' +b y' +c y = 0\) to solve for \(r\) we get:

\[(a r^2 +b r +c) e^{rt} = 0\]

\[\boxed{a r^2 +b r +c = 0 \text{ is called the \textbf{characteristic equation}.}}\]

The solutions to the characteristic equation are the exponents for \(y=e^{rt}\). There are always 2 solutions to a quadratic equation so if \(r_1\) and \(r_2\) are distinct real solutions to \(a r^2 +b r +c = 0\) then:

\[\boxed{y = C_1 e^{r_1 t} +C_2 e^{r_2 t}}\]

where \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are arbitrary constants, is the solution to \(a y'' +b y' +c y = 0\).

If \(r_1\) and \(r_2\) are repeated real solutions or complex solutions then we will deal with that later.

Step 1: Solve the characteristic equation.

\[r^2 +2r -3 = 0\]

Step 2: Write down the solution. \(y = C_1 e^{r_1 t} +C_2 e^{r_2 t}\)

\[\boxed{y = C_1 e^{-3 t} +C_2 e^{t}}\]

Step 1: Solve the characteristic equation.

\[6r^2 -5r +1 = 0\]

Step 2: Write the solution: \(y = C_1 e^{r_1 t} +C_2 e^{r_2 t}\)

Step 3: Solve for the constants \(C_1\) and \(C_2\)

3.4 Repeated Roots and Reduction of Order

Recall: 2nd order differential equation \(ay''+by'+cy=0\) has characteristic equation:

\[ar^2+br+c = 0\]

with solutions:

\[r = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2-4ac}}{2a} = r_1 \text{ and } r_2\]

There are three cases for these roots:

Case 1: \(b^2-4ac>0\) gives two distinct real roots \(r_1\) and \(r_2\)

The solutions to \(ay''+by'+cy=0\) are \(y_1=C_1 e^{r_1 t}\) and \(y_2= C_2 e^{r_2 t}\). You can put them together to get the general solution:

\[y=C_1 e^{r_1 t} +C_2 e^{r_2 t}\]

Case 2: \(b^2-4ac < 0\) gives two complex conjugate solutions \(r_1 = \alpha + \beta i\) and \(r_2 = \alpha - \beta i\)

The solutions to \(ay''+by'+cy=0\) are discussed in section 3.5.

Case 3: \(b^2-4ac = 0\) gives 1 repeated root \(r\).

The two solutions to \(ay''+by'+cy=0\) are \(y_1=C_1 e^{r t}\) and \(y_2 = ?\)

If we know one solution to a differential equation we can find a second solution using a technique known as Reduction of Order.

Suppose we know one solution \(y_1\) to the equation \(y''+ p(t) y'+ q(t) y = 0\) then to find a linearly independent second solution we can use a nonconstant multiple of our original solution.

Let:

\[y_2(t) = v(t) y_1(t)\]

Or if you don’t want to use as much the function notation you can abbreviate it as:

\[y_2 = v(t) y_1\]

Since we want this to be a solution to the equation \(y''+ p(t) y'+ q(t) y = 0\) we will need two derivatives:

\[y_2' = v(t) y_1' + v'(t) y_1\]

\[y_2'' = v(t) y_1'' + v'(t) y_1' + v'(t) y_1' + v''(t) y_1\]

We will substitute \(y_2\), \(y_2'\) and \(y_2''\) back into the original equation to get:

\[y_2''+ p(t) y_2'+ q(t) y_2 = 0\]

\[v(t) y_1'' + 2v'(t) y_1' + v''(t) y_1 + p(t) \left( v(t) y_1' + v'(t) y_1 \right)+ q(t) \left( v(t) y_1 \right) = 0\]

Simplify and combine the terms by \(v''(t)\), \(v'(t)\) and \(v(t)\) we see that:

\[v''(t) y_1 + \left( 2 y_1' + p(t) y_1 \right) v'(t) + \left( y_1''+ p(t) y_1'+ q(t) y_1 \right) v(t) = 0\]

This leaves us with the first order differential equation:

\[y_1 v''(t) + \left( 2 y_1' + p(t) y_1 \right) v'(t) = 0\]

Which is simply a first order differential equation in \(v'(t)\). We can solve this equation for \(v'(t)\) using the techniques we learned in Chapter 2 and then we can integrate to find \(v(t)\).

Then we have our second solution:

\[y_2 = v(t) y_1\]

Start with the characteristic equation: \(4r^2+12r+9 = 0\)

Using this r we can write our solutions:

\[y_1 = C_1 e^{-3t/2} \quad \text{and} \quad y_2 = v(t) e^{-3t/2}\]

Substitute \(y_2\), \(y_2'\) and \(y_2''\) back into the original equation

In general:

3.5 Complex Roots of the Characteristic Equation

Recall:

\[\begin{align*} e^{i\theta} & = \cos \theta + i \sin \theta \\ e^{-i\theta} & = \cos (-\theta) + i \sin (-\theta) \\ & = \cos \theta - i \sin \theta \end{align*}\]

We will use these formulas to convert complex roots of \(ay''+by'+cy=0\) to real solutions.

If \(r = \alpha \pm \beta i\) are the solutions to the characteristic equation then we know how to write the general solution:

\[y=C_1 e^{(\alpha + \beta i)t} +C_2 e^{(\alpha - \beta i) t}\]

but this is not a useful form. We want real solutions. We are going to use the identities at the top of the page to convert this into the form:

\[y = e^{\alpha t} \left(A\cos \beta t + B \sin \beta t \right)\]

\[e^{(\alpha + \beta i)t} = e^{\alpha t}e^{ \beta i t} = e^{\alpha t} \left( \cos \beta t + i \sin \beta t \right)\]

\[e^{(\alpha - \beta i)t} = e^{\alpha t}e^{ -\beta i t} = e^{\alpha t} \left( \cos \beta t - i \sin \beta t \right)\]

So the general solution is:

\[y = C_1 e^{\alpha t} \left( \cos \beta t + i \sin \beta t \right) + C_2 e^{\alpha t} \left( \cos \beta t - i \sin \beta t \right)\]

Since \(i\) is a constant this simplifies to:

\[y = e^{\alpha t} \left(A\cos \beta t + B \sin \beta t \right)\]

Step 1: Characteristic equation

Step 2: Write the solution. Here \(\alpha\) = -1 and \(\beta\) = 1

We would like to be able to write the solution:

\[y = A e^{\alpha t} \cos \beta t + Be^{\alpha t} \sin \beta t \tag{3.2}\]

as one trigonometric function of the form:

\[y(t) = R e^{\alpha t} \cos (\beta t - \delta)\]

Where \(R e^{\alpha t}\) is the amplitude and \(\delta\) is the phase angle. Using a trigonometric identity we can expand this to be:

\[y = R e^{\alpha t} \cos \delta \cos \beta t + R e^{\alpha t} \sin \delta \sin \beta t \tag{3.3}\]

Set the two equations (3.2) and (3.3) equal to each other.

\[R e^{\alpha t} \cos \delta \cos \beta t + R e^{\alpha t} \sin \delta \sin \beta t = A e^{\alpha t} \cos \beta t + Be^{\alpha t} \sin \beta t\]

\(e^{\alpha t}\) cancels on both sides and we can solve for \(R\) and \(\delta\) with the two equations:

\[R \cos \delta = A \qquad \text{and} \qquad R \sin \delta = B\]

square both and add them together to get:

\[R^2 \cos^2 \delta + R^2 \sin^2 \delta = A^2 + B^2\]

So \(\boxed{R = \sqrt{A^2 +B^2}}\)

To solve for \(\delta\) you divide the equations to get \(\boxed{\tan \delta = \frac{B}{A}}\)

Be sure to pick the correct \(\delta\) since there are two choices.

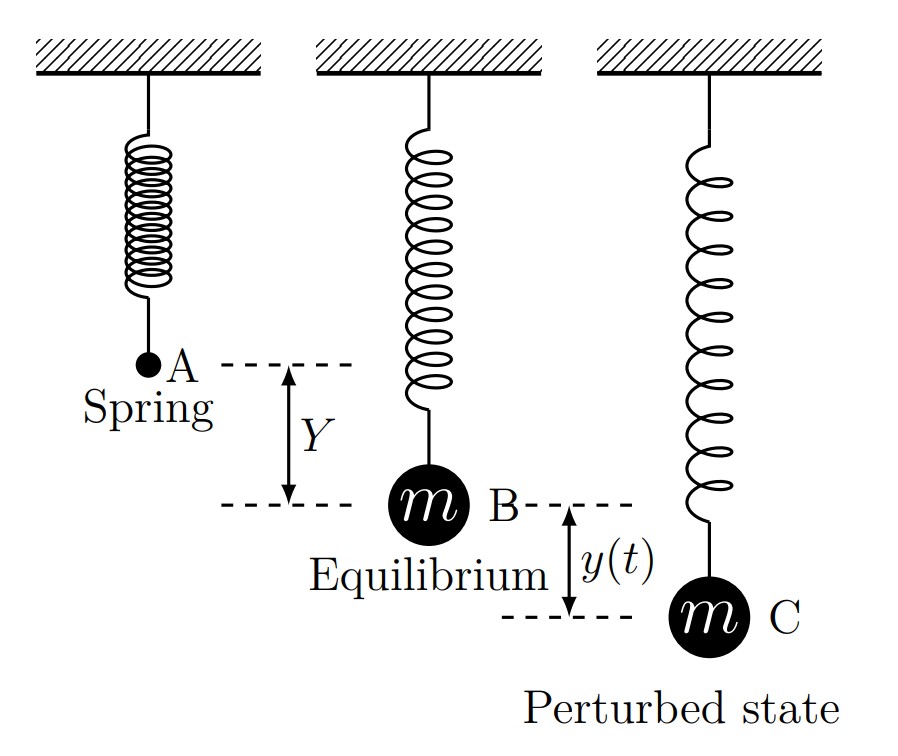

3.6 Unforced Mechanical Vibrations

Consider the spring and mass system shown here:

\(Y\) is the elongation of the spring in the downward direction caused by the mass \(m\). The function \(y(t)\) is the distance traveled by the mass from the equilibrium position. The spring constant is \(k\).

If we do not know the value of \(k\) we can solve for it. From physics we know that the force of the spring is nearly proportional to \(Y\). So at equilibrium we can write the following equations to solve for \(k\):

\[\begin{align*} F & = kY\\ mg & = kY\\ k & = \frac{mg}{Y} \end{align*}\]

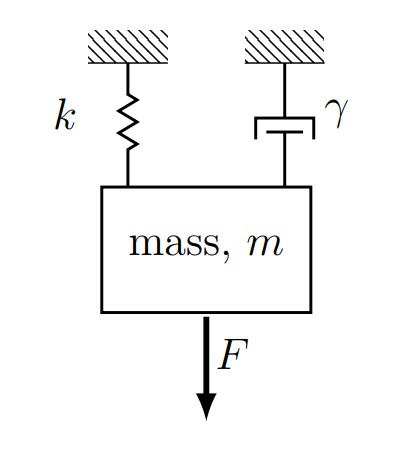

In reality all systems have some amount of damping so the usual spring-mass-damper system can be modeled as follows: \(k\) is the spring constant, \(\gamma\) is the damping constant, and \(m\) is the mass.

From our free body diagram we can find the forces acting on the mass:

| Force | Expression | Direction |

|---|---|---|

| Force of the spring | \(k[Y+y(t)]\) | \(\uparrow\) |

| Force of gravity | \(mg\) | \(\downarrow\) |

| Force of damper | \(\gamma y'(t)\) | \(\uparrow\) |

| Some external forcing function: | \(F(t)\) |

Using the standard formula \(\sum F = m a = m y''(t)\) to get a differential equation:

\[\begin{align*} m g - k[Y+y(t)] -\gamma y'(t) + F(t) &= my''(t) \\ my''(t) + \gamma y'(t) +k y(t) &= F(t) \end{align*}\]

\[my''(t) + \gamma y'(t) +k y(t) = F(t) \tag{3.4}\]

Units: The units all have to be force units so:

| Constants | Other units |

|---|---|

| \(k = \frac{\text{force}}{\text{displacement}} = \frac{\text{kg}}{s^2}\) | force: lbs, N, \(\frac{\text{kg} \cdot \text{m}}{\text{s}^2}\) |

| displacement: m, ft, etc. | |

| \(\gamma = \frac{\text{force}}{\text{speed}} = \frac{\text{kg}}{s}\) | speed: \(\frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}}\), \(\frac{\text{ft}}{\text{s}}\), etc. |

The characteristic equation for (3.4):

\[m r^2 +\gamma r + k = 0\]

has solutions:

\[r = \frac{-\gamma \pm \sqrt{\gamma^2 - 4 m k}}{2m}\]

There are 3 possible outcomes:

| Discriminant | Type | Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| \(\gamma^2 - 4 m k < 0\) | Complex solutions | Underdamped, oscillation |

| \(\gamma^2 - 4 m k = 0\) | One repeated solution | Critically damped, no oscillation |

| \(\gamma^2 - 4 m k > 0\) | Two negative real solutions | Overdamped, no oscillation |

Step 1: Draw a picture and identify what you know including Initial Conditions:

Step 2: Write down a useful equation(s):

\[my''+ky = 0\]

Step 3: Solve:

\[y(t)= 2 \cos(14 t) + \frac{5}{7} \sin (14t) \tag{3.5}\]

We would like to be able to write equation (3.5) as one trigonometric function of the form:

\[y(t) = R \cos(\mu t - \delta)\]

Where \(R\) is the amplitude or maximum displacement of our vibration, \(\mu\) is the natural frequency (Hz) of the vibration and \(\delta\) is the phase angle. If we expand that with the cosine angle difference identity (\(\cos (A-B) = \cos A \cos B + \sin A \sin B\)) what we get is something of the form:

\[y(t) =R \cos \delta \cos (\mu t) + R \sin \delta \sin (\mu t) \tag{3.6}\]

We can compare the identity (equation 3.6) to the answer (equation 3.5).

\[R \cos \delta \cos (\mu t) + R \sin \delta \sin (\mu t) = 2 \cos(14 t) + \frac{5}{7} \sin (14t)\]

and solve for \(R\) and \(\delta\). Assuming that \(\mu = 14\) we can compare the coefficients:

\[R \cos \delta = 2 \qquad \text{and} \qquad R \sin \delta = \frac{5}{7}\]

Then:

\[R^2 \cos^2 \delta + R^2 \sin^2 \delta = R^2 = 2^2 + \left(\frac{5}{7}\right)^2 \implies \boxed{R = \frac{\sqrt{221}}{7}}\]

\(\delta\) can be found by taking the quotient of the two equations:

\[\frac{R \sin \delta}{R \cos \delta} = \tan \delta = \frac{5}{14} \implies \boxed{\delta = \tan^{-1} \left(\frac{5}{14} \right)}\]

The final solution is:

\[\boxed{y(t) = \frac{\sqrt{221}}{7} \cos(14t - \delta)}\]

3.7 The General Solution of a Linear Nonhomogeneous Equation

Given the differential equation:

\[y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=g(t) \tag{3.7}\]

we know that this is nonhomogeneous if \(g(t) \neq 0\). For every nonhomogeneous equation there is a corresponding homogeneous equation:

\[y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=0 \tag{3.8}\]

Suppose that \(Y_1\) and \(Y_2\) are two solutions to the nonhomogeneous equation (3.7) and \(\{y_1, y_2\}\) are a fundamental set of solutions for the corresponding homogeneous equation (3.8), then:

\[Y_1 - Y_2 = C_1 y_1 +C_2y_2\]

Translation: There is only ONE particular solution to any nonhomogeneous differential equation.

3.8 The Method of Undetermined Coefficients

The solution to every differential equation \(y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=g(t)\) is always of the form:

\[y = y_h +y_p\]

where \(y_h\) is the homogeneous solution and \(y_p\) is the particular solution.

There are always 3 steps to solving \(y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=g(t)\):

Step 1: Find the homogeneous solution \(y_h = C_1 y_1 +C_2y_2\).

Step 2: Find the particular solution \(y_p\).

Step 3: Add them together \(y = y_h + y_p = C_1 y_1 +C_2y_2 + y_p\)

We know how to do Step 1: Solve the characteristic equation.

We know how to do Step 3.

How are we going to find the particular solution?

Answer: Guess a solution that looks like your answer \(g(t)\).

This is known as the Method of Undetermined Coefficients.

The initial guess for the method of undetermined coefficients to solve the differential equation:

\[ay'' +by' +cy = g_i(t)\]

is summarized in the following table. The first column is the form of \(g_i(t)\) and the second column is the form of the particular solution \(Y_i(t)\). Notice that each equation has \(t^s\). Choose \(s\) to be the smallest integer such that NO term of \(Y_i(t)\) is a solution to the homogeneous equation.

| \(g_i(t)\) | \(Y_i(t)\) |

|---|---|

| \(P_n(t) = a_n t^n + \cdots + a_1 t +a_0\) | \(t^s [A_n t^n + \cdots + A_1 t +A_0]\) |

| \(P_n(t) e^{\alpha t}\) | \(t^s [A_n t^n + A_{n-1} t^{n-1} + \cdots + A_1 t +A_0] e^{\alpha t}\) |

| \(P_n(t) e^{\alpha t} \sin(\beta t)\) or \(P_n(t) e^{\alpha t} \cos(\beta t)\) | \(t^s [A_n t^n + \cdots + A_1 t +A_0] e^{\alpha t} \sin(\beta t) +\) \(t^s [B_n t^n + \cdots + B_1 t +B_0] e^{\alpha t} \cos(\beta t)\) |

3.9 Variation of Parameters (The Plow Method)

There are always 3 steps to solving the differential equation:

\[y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=g(t)\]

Step 1: Find the homogeneous solution. \(y_h = C_1 y_1 + C_2 y_2\).

Step 2: Find the particular solution: \(y_p\)

Step 3: Add them together: \(y = y_h + y_p = C_1 y_1 + C_2 y_2 +y_p\)

In Section 3.8 we saw that we could guess at a solution that looked like the answer. That is fine if your answer is nice but it doesn’t always work well. Variation of parameters is a completely general form that applies to all situations. However, it isn’t always possible to solve the problem explicitly because in the end there are always integrals to be evaluated.

Variation of Parameters:

Start with \(y''+p(t)y'+q(t)y=g(t)\)

Step 1: Solve the homogeneous equation for the family of solutions \(\{y_1, y_2\}\)

Step 2: Let the particular solution have the form:

\[y_p = u_1(t) y_1 + u_2(t) y_2\]

where \(u_1(t)\) and \(u_2(t)\) are functions that we will determine. To solve for \(u_1\) and \(u_2\) we need to find \(y_p'\) and \(y_p''\) and substitute back into the original equation. Don’t forget the product rule.

\[y_p' = u_1 y_1' + u_1' y_1 + u_2 y_2' + u_2' y_2\]

Now at this point we have generated 4 terms and 4 unknown values (\(u_1\), \(u_2\), \(u_1'\) and \(u_2'\)) so we need to put some constraints on the system. There are many choices we could make here but the best choice is to assume that:

\[u_1' y_1 + u_2' y_2 = 0 \tag{3.9}\]

This equation will be one that we will use to solve for \(u_1\) and \(u_2\) and with this constraint the derivative simplifies to \(y_p' = u_1 y_1' + u_2 y_2'\). Now take a second derivative:

\[y_p'' = u_1 y_1'' + u_1' y_1' + u_2 y_2'' + u_2' y_2'\]

Now put \(y_p\), \(y_p'\) and \(y_p''\) back into the original differential equation and simplify:

\[\begin{align} g(t) &= y_p''+p(t)y_p'+q(t)y_p \\ &= u_1 y_1'' + u_1' y_1' + u_2 y_2'' + u_2' y_2' + p(t) [u_1 y_1' + u_2 y_2']+q(t) [u_1 y_1 + u_2 y_2] \\ &= u_1 y_1'' + p(t) u_1 y_1' + q(t) u_1 y_1 + u_2 y_2'' + p(t) u_2 y_2'+q(t) u_2 y_2 +u_1' y_1'+ u_2' y_2' \\ &= u_1( y_1'' + p(t) y_1' + q(t) y_1) + u_2( y_2'' + p(t) y_2'+q(t) y_2) +u_1' y_1'+ u_2' y_2' \end{align}\]

Which simplifies to:

\[g(t) = u_1' y_1'+ u_2' y_2' \tag{3.10}\]

Now we can solve equations (3.9) and (3.10) for \(u_1\) and \(u_2\):

\[\begin{align*} u_1' y_1+u_2' y_2 &= 0\\ u_1' y_1'+u_2' y_2' &= g(t) \end{align*}\]

Solving this system is straightforward. Solve the first for \(u_1'\) and plug that into the second and simplify a little as follows:

\[\begin{align*} u_1' &= -\frac{u_2'y_2}{y_1}\\ g(t) &= \left(-\frac{u_2'y_2}{y_1}\right)y_1'+u_2'y_2'\\ g(t) &= u_2'\left(y_2'-\frac{y_2y_1'}{y_1}\right)\\ u_2'(t) &= \frac{y_1g(t)}{y_1y_2'-y_2y_1'} \end{align*}\]

After plugging this back into \(u_1\) we get:

\[u_1'=-\frac{y_2g(t)}{y_1y_2'-y_2y_1'}\]

Now, recall that if \(\{y_1, y_2\}\) form a fundamental set of linearly independent solutions to the characteristic equation, then the Wronskian will not equal zero. So, finally we need to integrate \(u_1'\) and \(u_2'\):

\[u_1=-\int \frac{y_2g(t)}{y_1 y_2'-y_2y_1'}, \qquad u_2=\int \frac{y_1g(t)}{y_1y_2'-y_2y_1'}\]

These results are summarized here:

Step 1: Solve homogeneous equation \(y'' +9y = 0\)

\[y_h = C_1 \cos 3t +C_2 \sin 3t\]

Solution: For the particular solution we will guess:

\[y_p = v(1+t)+u(e^t)\]

3.10 Forced Mechanical Vibrations

The nonhomogeneous case of Section 3.6.

In these problems we have some external forcing function driving the system. The forcing function can be almost anything but usually it is periodic.

\[F(t)=F_1 \cos (\omega t) + F_2 \sin (\omega t)\]

So our equation looks like:

\[\begin{align*} my''(t) + \gamma y'(t) +k y(t) &= F(t)\\ my''(t) + \gamma y'(t) +k y(t) &= F_1 \cos (\omega t) + F_2 \sin (\omega t) \end{align*}\]

and the solution is once again:

\[y(t) = y_h(t)+y_p(t) \tag{3.11}\]

where \(y_h(t)\) is the homogeneous solution and \(y_p(t)\) is the particular solution.

Two cases here:

I. If there is no damping (i.e. \(\gamma = 0\)) then the solutions to (3.11) are of the form:

\[\begin{align*} y_h(t) &= C_1 \cos (\omega_0 t)+C_2 \sin (\omega_0 t)\\ \\ y_p(t) &= \begin{cases} A \cos (\omega t)+ B \sin (\omega t) & \text{when } \omega \neq \omega_0\\ A t\cos (\omega t)+ B t\sin (\omega t) & \text{when } \omega = \omega_0 \end{cases} \end{align*}\]

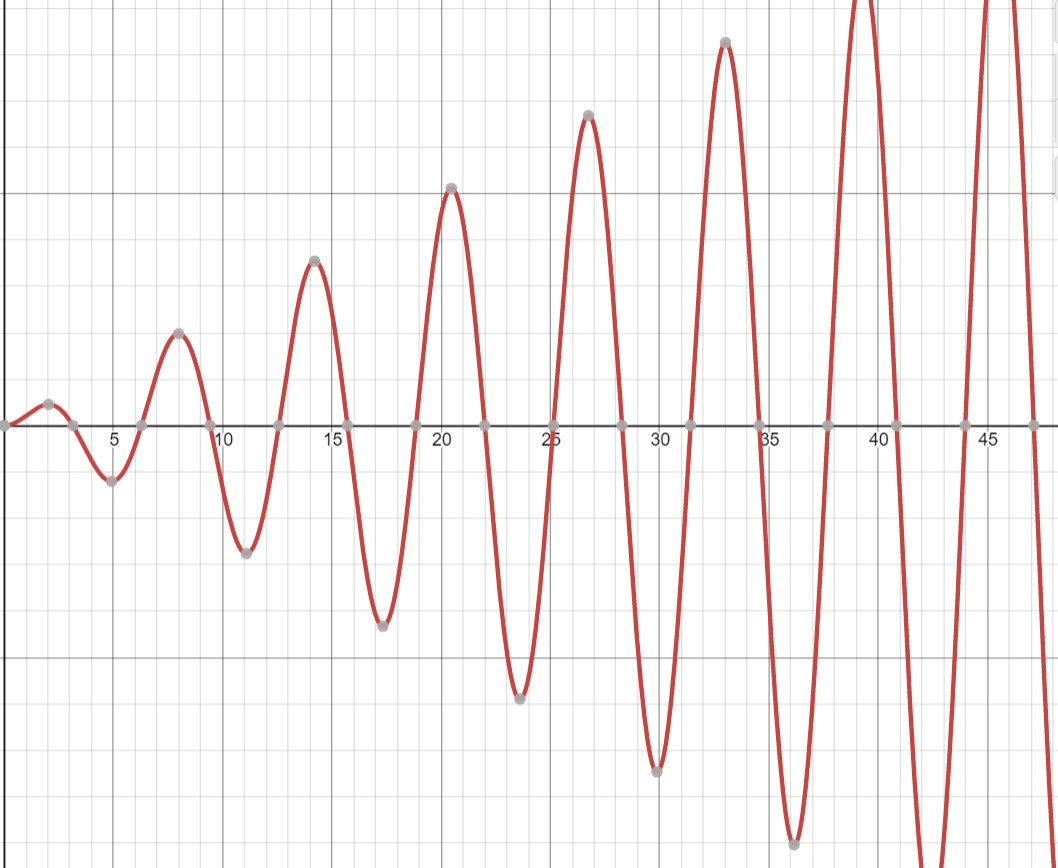

The second case \(\omega = \omega_0\) is known as resonance. When the frequency of the forcing function is the same as the natural frequency of the system then the motion of the system is unbounded as \(t \rightarrow \infty\).

Figure 3.1: \(y=0.25 t \sin t\) - Resonance behavior showing unbounded oscillation

II. If \(\gamma\) is not zero then our solutions all have an \(e^{-rt}\) component in the homogeneous solutions (\(y_h(t)\)). The total solution is:

\[y(t)=y_h(t)+y_p(t)\]

and as \(t \rightarrow \infty\) the homogeneous part, called the transient solution, goes to zero so in the long term you are only left with the particular solution. The particular solution is therefore called the steady state solution or forced response.

3.11 Higher Order Linear Homogeneous Differential Equations

Existence and Uniqueness

We need \(n\) initial conditions to solve an initial value problem (IVP) here. As in the 2nd order case we will find \(n\) linearly independent solutions to the homogeneous equation. We can still determine linear independence by calculating the Wronskian.

\[W=\begin{vmatrix} y_1 & y_2 & \cdots & y_n\\ y'_1 & y'_2 & \cdots & y'_n\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ y^{(n-1)}_1 & y^{(n-1)}_2 & \cdots & y^{(n-1)}_n \end{vmatrix}\]

If \(W\neq0\) then \(y_1, y_2, \ldots, y_n\) are linearly independent and form a fundamental set of solutions for:

\[y^{(n)} +p_{n-1}y^{(n-1)} + \cdots + p_2(t) y'' + p_1(t) y' +p_0(t) y = 0\]

For the nonhomogeneous case there is still only one particular solution \(y_p\) and the total solution is:

\[Y(t) = y_h(t) + y_p(t)\]

Recall: A set of solutions is a fundamental set of solutions if every solution of the differential equation can be represented as a linear combination of the elements of the set.

Why do we care about Abel’s Theorem? Because it says that if the Wronskian is not zero at any point of \((a, b)\) then it is not zero at every point of \((a, b)\).

Linearly independent essentially means that the functions \(f_1(t), f_2(t), \ldots, f_r(t)\) are all different, while dependent sets are not really different.

Part 1: \(y_1(1)=2\), \(y'_1(1)=2\), \(y_2(1) = -1\), \(y'_2(1) = -1\)

Part 2: \(y_1(0)=0\), \(y'_1(0)=1\), \(y_2(0) = -1\), \(y'_2(0) = 0\)

3.12 Higher Order Homogeneous Constant Coefficient Differential Equations

Consider: \((-1)^{1/3} = -1\)

What about the solutions to \(x^3+1=0\)? There are three, \(x=-1\) is one, so where are the other two?

Try \(x = \frac{1+i\sqrt{3}}{2}\):

\[\left( \frac{1+i\sqrt{3}}{2}\right)^3 + 1 = 0\]

So the third solution is:

In order to find these solutions in the complex plane you need to start with Euler’s formula:

\[e^{i\theta} = \cos \theta + i \sin \theta\]

For this example we can write \(-1\) as a complex number:

\[-1 = e^{\pi i} = \cos \pi + i \sin \pi\]

But we could have also written this more generically:

\[-1 = e^{(\pi + 2n\pi)i}, \qquad n \in \mathbb{Z}\]

So if we want three solutions to \((-1)^{1/3}\) we can use the complex form:

\[(-1)^{1/3} = \left( e^{(\pi + 2n\pi)i} \right)^{1/3} = e^{(\pi/3 + 2n\pi/3)i}, \qquad n = 0, 1, 2\]

which provides three distinct answers:

\[(-1)^{1/3} = e^{\pi i/3}, e^{\pi i}, e^{5\pi i/3}\]

These can be graphed in the Real-Imaginary plane.

We can use this to solve differential equations of higher order.

The procedure is the same as for second order equations. We assume that our solution looks like \(y = e^{r_it}\) where \(r_i\) is a solution to the characteristic equation:

\[r^4 - 8r = 0\]

\[r(r^3 - 8) = 0\]

so either \(r = 0\) or \(r^3 - 8=0\)

The 4 solutions are \(r_1 = 0\), \(r_2 = 2\), \(r_3 = -1+\sqrt{3} i\), \(r_4 = -1 - \sqrt{3} i\) and the complete solution is: