Chapter 2 First Order Differential Equations Notes, Kohler & Johnson 2e

2.1 First Order Equations - Existence and Uniqueness Theorems

A differential equation of the form:

\[y'+p(t)y=g(t) \tag{2.1}\]

is called a first order linear differential equation.

Equation (2.1) is called homogeneous if \(g(t) = 0\).

Equation (2.1) is called nonhomogeneous if \(g(t) \neq 0\).

Given the initial value problem \(y'+p(t)y=g(t)\), \(y(t_0)=y_0\) several questions arise:

Under what circumstances can we be sure the equation has a solution passing through the given point?

Is it possible for an equation to have more than one solution through an initial point? Or equivalently, if we find a solution passing through a point, can we be sure it is the only solution?

Applied to (a), (b), (c), and (d)?

Consider the following first order linear differential equations. For each of the initial conditions, determine the largest interval \(a < t < b\) on which the Existence-Uniqueness Theorem guarantees the existence of a unique solution.

2.2 Linear First Order Differential Equations

First Order Linear Homogeneous Equations

Consider a linear first order differential equation of the form:

\[y'+p(t)y=g(t) \tag{2.2}\]

where \(p(t)\) and \(g(t)\) are continuous functions on some interval \(a \leq t \leq b\). We will begin by solving this equation for the homogeneous case (\(g(t) =0\)).

We would like to find a function whose derivative is close to the original function. A good choice is \(y=e^{h(t)}\). The trick will be to choose \(h(t)\) appropriately so let’s try our choice for \(y\) in the original function and see what happens. We will need a derivative first:

\[y' = h'(t) e^{h(t)}\]

Now we substitute into equation (2.2) to get:

\[h'(t) e^{h(t)} + p(t) e^{h(t)} = 0\]

\[h'(t) e^{h(t)} =- p(t) e^{h(t)}\]

\[h'(t) =- p(t)\]

Taking a few liberties with the notation we can integrate both sides to solve for \(h(t)\):

\[h(t) = \int h'(t) dt = - \int p(t) dt\]

And our solution to the first order homogeneous differential equation is:

\[y = e^{- \int p(t) dt} \tag{2.3}\]

In general they are not so easy.

We need to fix the equation so it has the correct form: \(y'+p(t)y=0\)

Choose \(y = e^{- \int 2t dt} =e^{-t^2+c}\)

First Order Linear Nonhomogeneous Equations

The Product Rule and Integration by Parts:

Recall: Product Rule: \(d[uv] = uv' +vu'\) or \(d[uv] = udv +vdu\)

We can rewrite this as \(d[uv] - v du =u dv\) and integrate both sides:

\[\int d[uv] - \int v du = \int u dv\]

to get \(\boxed{\displaystyle uv - \int v du = \int u dv}\) Integration by Parts

Also from the product rule we can get:

\[uv = \int (udv +vdu) \tag{2.4}\]

We will use equation (2.4) with a change of variables to solve differential equations.

If we start with a differential equation of the form: \(y' + p(t) y = 0\) then we could easily integrate it if we could write it in the form: \[u(t) y' + u'(t) y = 0\] for some appropriate \(u(t)\) since this is in the form of the right hand side of equation (2.4).

What do we mean by “appropriate”?

We need to multiply by some function \(u(t)\) so that: \[u(t) y' + \underbrace{u(t) p(t)}_{=u'(t)} y = 0\]

We will choose: \[u(t) = e^{\int p(t) dt} = e^{P(t)} \tag{2.5}\]

and this is called the integrating factor. To see why this is a good choice of \(u(t)\) notice that \(u'(t) = p(t) e^{\int p(t) dt} = p(t) u(t)\). If we take our original differential equation \(y' + p(t) y = 0\) and multiply by \(u(t)\) we get:

\[u(t) y' + u(t) p(t) y = u(t) y' + u'(t)y\]

\[\frac{d}{dt}(u(t) y(t))=0 \tag{2.6}\]

which is what we wanted. Integrating both sides of equation (2.6) we have a solution: \[u(t) y(t) = C\]

If the original equation is not homogeneous: \[y' + p(t) y = g(t)\]

we can still multiply by the integrating factor: \(u(t) = e^{\int p(t) dt}\)

Steps for solving nonhomogeneous equation \(y' + p(t) y = g(t)\)

Write \(y'+p(t)y=g(t)\)

Find the integrating factor: \(u(t)=e^{\int p(t) dt}\)

Multiply by the integrating factor: \[u(t)(y'+p(t)y)=u(t) \cdot g(t)\]

Recognize that you have \(\displaystyle \frac{d}{dt} [u \cdot y] = u(t) \cdot g(t)\)

Integrate: \(uy=\displaystyle \int \frac{d}{dt} [u \cdot y] = \int u(t) \cdot g(t) dt\)

Choose \(u = \displaystyle e^{\int 2t dt} = e^{t^2+c}\). What do we do with \(c\)?

First put the equation in the correct form. The coefficient of \(y'\) must be 1.

2.3 Mixing Problems and Cooling Problems

2.4 Population Dynamics and Radioactive Decay

Since the amount decreases at a rate proportional to the current amount we can write our differential equation as:

\[\frac{dy}{dt} = -0.02828 y(t) + 3 \tag{2.7}\]

The important thing to check is your units. \(dy/dt\) is mg/day and the amount being added is mg/day so the units agree.

Solving the differential equation (2.7) is fairly straight forward using the integrating factor.

\[y'+0.02828 y(t) = 3\]

Multiply by the integrating factor \(u = e^{0.02828t}\) to get:

\[e^{0.02828t}y'+0.02828e^{0.02828t} y(t) = 3e^{0.02828t}\]

Integrate:

\[\int \left( e^{0.02828t}y'+0.02828e^{0.02828t} y(t) \right) dt= \int 3e^{0.02828t}dt\]

\[e^{0.02828t}y= \frac{3}{0.02828}e^{0.02828t} + C\]

Solve for \(y(t)\) to get:

\[y= \frac{3}{0.02828} + Ce^{-0.02828t}\]

Apply the initial condition \(y(0)=200 = \frac{3}{0.02828} +C\) so \(C= 93.9\) and our final answer is:

\[y= \frac{3}{0.02828} + 93.9e^{-0.02828t} \tag{2.8}\]

2.5 First Order Nonlinear Differential Equations

Given the initial value problem \(y'=f(t,y)\), \(y(t_0)=y_0\) several questions arise:

Under what circumstances can we be sure the equation has a solution passing through the given point?

Is it possible for an equation to have more than one solution through an initial point? Or equivalently, if we find a solution passing through a point, can we be sure it is the only solution?

Autonomous Differential Equations:

First order autonomous differential equations have the form \(y' = f(y)\). If you have two different initial conditions for \(y' = f(y)\) you will get two different solutions: \(y_1(t)\) and \(y_2(t)\). The following theorem shows that the solution \(y_2(t)\) is related to the solution \(y_1(t)\) by:

\[y_2(t) = y_1(t-c) \tag{2.9}\]

where \(c\) is a constant.

2.6 Separable Equations

Separable means we can group the \(x\)’s and \(y\)’s separately. Usually solved by integration.

Rewrite and integrate

If you remember \(\displaystyle \int \frac{dy}{1+y^2} dy = \tan^{-1} y\) then this is finished. Otherwise you can try a substitution such as \(y = \tan u\) and \(dy = \sec^2 u du\)

2.9 One Dimensional Motion with Air Resistance

The equation of the forces acting on an object is:

\[\sum F = ma\]

If we have a falling object with air resistance then we can construct a differential equation to describe the motion. Usually the force of air resistance is proportional to the velocity (or the velocity squared).

Here \(\gamma\) depends on the properties of the falling object. Here we will assume that positive acceleration/velocity/position is upward.

\[m \frac{dv}{dt}= -mg-\gamma v, \qquad v(0) = v_0\]

\[m \frac{dv}{dt}= -mg-kv^2, \qquad v(t) > 0\]

\[m \frac{dv}{dt}= -mg+kv^2, \qquad v(t) < 0\]

One-Dimensional Dynamics with Distance as the Independent Variable

\[\frac{dv}{dt} = \frac{dv}{dx}\frac{dx}{dt} = v \frac{dv}{dx}\]

Using this formula we can change an equation from being velocity as a function of time to velocity as a function of distance.

2.10 Euler’s Method (Tangent Lines)

Euler’s method is a numerical approximation to a differential equation using tangent lines. This method is easy to implement because we know that the slope of the line is y’ and we have a starting point \((x_0, y_0)\).

Recall (from Algebra I): The equation of a line using the point slope formula.

If \(m =\) slope and \((x_0, y_0)\) = a point then the equation of the line is given by:

\[y-y_0=m(x-x_0)\]

or

\[y=y_0+m(x-x_0)\]

If we start with a differential equation initial value problem how does this apply?

Start with the IVP:

\[\frac{dy}{dx} = f(t,y); \qquad y(t_0)=y_0\]

then \(f(t,y)\) = slope and \((t_0, y_0)\) = point.

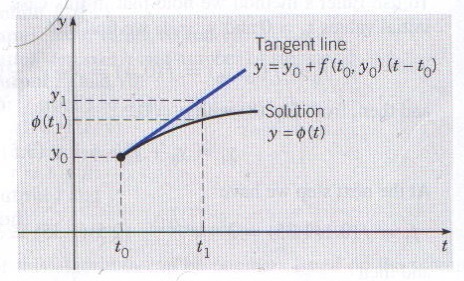

We can approximate the solutions near that point by a straight line approximation:

\[y=y_0+f(t_0, y_0)(t-t_0)\]

Figure 1: A tangent line approximation

As long as we stay close to \((t_0, y_0)\) this approximation is good, however, we would like to be able to approximate the value of \(y\) at any time \(t\). To do this we will find a linear approximation at the point \(t_1\) which is close to \(t_0\) and then, using that point, we will find an approximation for \(t_2\) which is close to \(t_1\) and so on. We still don’t know the function \(y(t)\) so we don’t know the \(y\) value at \(t_1\) but we can assume that if we use our linear approximation at \((t_0, y_0)\) this point will be close enough to the actual value of the function.

We are going to use the linear approximation to calculate the new \(y\)-value using the slope \(\frac{dy}{dx} = f(t_0,y_0)\). Then the new \(y\)-value is \(y_1=y_0+f(t_0, y_0)(t_1-t_0)\).

Using this new point \((t_1, y_1)\) we can approximate the solutions near \((t_1, y_1)\) using the line:

\[y=y_1+f(t_1, y_1)(t-t_1)\]

To find another point we use \(t_2\) to get \(y_2=y_1+f(t_1, y_1)(t_2-t_1)\).

In general we can find the point \((t_{n+1}, y_{n+1})\) by the following formula:

\[y_{n+1}=y_{n}+f(t_{n}, y_n)(t_{n+1}-t_n)\]

And if we let the difference \(t_{n+1}-t_n = h\) always be constant (\(h\)) then the formula reduces to:

\[y_{n+1}=y_n+f(t_n, y_n)h \tag{2.11}\]

The algorithm for the Euler Method is as follows:

Step 1: Define \(f(t,y)\)

Step 2: Input initial values of \(t_0\) and \(y_0\)

Step 3: Input step size \(h\) and the number of steps \(n\).

Step 4: Output \(t=t_0\) and \(y=y_0\)

Step 5: For \(j\) from 1 to \(n\) Do

Step 6: - \(k_1=f(t,y)\) - \(y=y+h \cdot k_1\) - \(t=t+h\)

Step 7: Output \(t\) and \(y\).

Step 8: End