Chapter 5 Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors, Linear Algebra 6e Lay

5.1 Eigenvectors and Eigenvalues

For this section we will assume that \(A\) is an \(n \times n\) matrix. So any transformation \(T(x) = Ax\) sends vectors from \(\mathbb{R}^n\) to \(\mathbb{R}^n\).

- Describe what this transformation does to the standard basis vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

- Let \(\mathfrak{b}_1 = \begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}\). Calculate \(T(\mathfrak{b}_1)\) and describe what happens.

- Let \(\mathfrak{b}_2 = \begin{bmatrix} -1 \\ 2 \end{bmatrix}\). Calculate \(T(\mathfrak{b}_2)\) and describe what happens.

In this section we will be given either an eigenvalue or an eigenvector for each problem.

- If \(Ax = \lambda x\) for some vector \(x\), then \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\).

- A matrix \(A\) is not invertible if and only if \(0\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) (\(Ax = 0x\)).

- A number \(c\) is an eigenvalue of \(A\) if and only if the equation \((A-c I)x =0\) has a nontrivial solution.

- To find the eigenvalues of \(A\), reduce \(A\) to echelon form.

- If \(Ax = \lambda x\) for some scalar \(\lambda\), then \(x\) is an eigenvector of \(A\).

- If \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are linearly independent eigenvectors, then they correspond to distinct eigenvalues.

- An eigenspace of \(A\) is a null space of a certain matrix.

- An \(n \times n\) matrix can have at most \(n\) eigenvalues.

5.2 The Characteristic Equation

The Eigenvalue Problem

We would like to find solutions to \[A\vec{x} = \lambda \vec{x}\] where \(\lambda\) is a constant. In these cases multiplication by the matrix is the same as multiplication by a constant. These constants (\(\lambda\)) are called eigenvalues and their associated vectors (\(\vec{x}\)) are called eigenvectors.

So how do we find eigenvalues and eigenvectors?

We want \(A\vec{x} = \lambda \vec{x}\) so:

\[\begin{align} A\vec{x} - \lambda \vec{x} &= 0 \\ (A - \lambda I) \vec{x} &= 0 \tag{1} \end{align}\]

We know this has nonzero solutions if and only if:

\[\det(A - \lambda I)=0 \tag{2}\]

Step 1: Solve equation (2) for the eigenvalues \(\lambda\).

Step 2: The eigenvectors are the solutions to equation (1) for a particular value of \(\lambda\).

Step 1: \((A - \lambda I) = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 3 \\ 4 & 2\end{bmatrix} - \lambda \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 - \lambda & 3 \\ 4 & 2 - \lambda \end{bmatrix}\)

\(\det(A - \lambda I)= (1 - \lambda)(2 - \lambda) - 12 =0\)

Step 2: Solve \((A - \lambda I) \vec{x} = 0\) for \(\vec{x}\)

Note that the factor \((7 -\lambda)\) and the eigenvalue \(\lambda = 7\) appear twice. The eigenvalue 7 is said to have multiplicity 2.

Eigenvalue Properties

5.3 Diagonalization

Diagonal matrices

Recall:

The characteristic equation of a square matrix \(A\), formally notated \(\det(A- \lambda I) = 0,\) is the equation obtained by subtracting the variable \(\lambda\) from the entries along the main diagonal of \(A\), then taking the determinant and setting it equal to zero.

The roots of this polynomial equation are the eigenvalues of \(A\). If a root is repeated \(k\) times, we say that eigenvalue has algebraic multiplicity \(k\).

Let D be a diagonal matrix (a square matrix in which all of the entries are zero, except possibly those on the main diagonal). Then computing powers of D are simple, as this example illustrates:

In general, \(D^k = \begin{bmatrix}5^k&0 \\ 0 & 3^k\end{bmatrix}\).

If \(A\) is not a diagonal matrix itself, but it is similar to a diagonal matrix \(D\), then \(A = PDP^{-1}\), for some invertible matrix \(P\). Then:

\[A^2 = (PDP^{-1})(PDP^{-1}) = PD^2 P^{-1}\]

In general, \(A^n = PD^n P^{-1}\).

Compare the number of multiplications required to compute each side of this equation when \(n\) is very large, and you’ll see that this formula can be quite efficient.

Diagonalizability

5.5 Complex Eigenvalues

Complex Arithmetic

Q: What is a complex number?

A: It is a number of the form \(a + bi\) where \(a\) and \(b\) are real numbers and \(i^2 = -1\).

- \(a\) is called the real part

- \(b\) is called the imaginary part.

- The conjugate of \(a + bi\) is \(a - bi\).

Properties

- \(a + b~i = c + d~i \qquad \Leftrightarrow \qquad a = c ~ \text{and} ~ b = d\)

- \((a + b~i) + (c + d~i) = (a + c) + (b + d)~i\)

- \((a + b~i) \cdot (c + d~i) = ac + ad~i + bc~i +bd~i^2 = (ac-bd)+(ad+bc)~i\)

- \((a+b~i)(a-b~i) = a^2 + b^2\)

Complex Numbers in Equations

Polar Form of a Complex Number

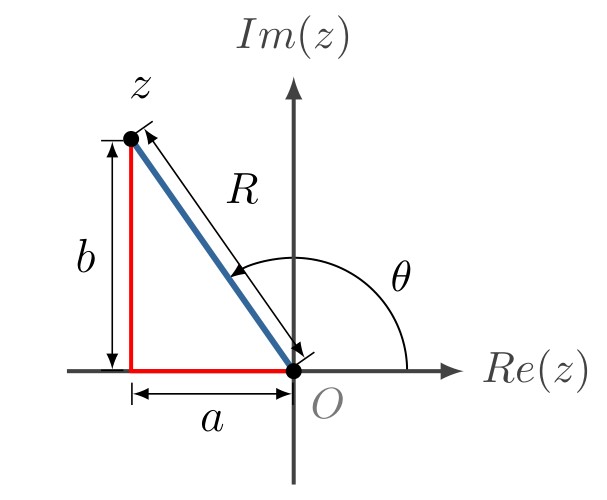

Euler’s formula allows us to plot complex numbers on the Re-Im plane. This is called an Argand Diagram. For example for a complex number of the form \(z=a+bi = Re^{i\theta}\) the Argand Diagram is shown below.

Solution:

\[C = r \begin{bmatrix} a/r & -b/r \\ b/r & a/r \end{bmatrix}\]